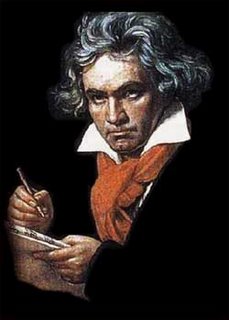

The year is 1982. I live in downtown Philadelphia across the street from The Academy of Music, where The Philadelphia Orchestra performs. I am now enough of a music fan that I buy a twenty-five-dollar ticket to hear a famous orchestra play the "Eroica," Beethoven's third symphony, live. It is not a very heroic experience. I feel dispirited from the moment I walk in the hall. My black jeans draw disapproving glances from men who seem to be modeling the Johnny Carson collection. I look around dubiously at the twenty shades of red in which the hall is decorated. The music starts, but I find it hard to think of Beethoven's detestation of all tyranny over the human mind when the man next to me is a dead ringer for my dentist. The assassination sequence in the first movement is less exciting when the musicians have no emotion on their faces. I cough; a thin man, reading a dog-eared score, glares at me. When the movement is about a minute from ending, an ancient woman creeps slowly up the aisle, a look of enormous dissatisfaction on her face, followed at a few paces by a blank-faced husband. Finally, three grand chords to finish, which the composer obviously intended to set off a roar of applause. I start to clap, but the man with the score glares again. One does not applaud in the midst of greatly great great music, even if the composer wants to! Coughing, squirming, whispering, the crowd visibly suppresses its urge to express pleasure. It's like mass anal retention. The slow tread of the Funeral march, or Marcia funebre, as everyone insists on calling it, begins. I start to feel that my newfound respect for the music is dragging along behind the hearse.

The year is 1982. I live in downtown Philadelphia across the street from The Academy of Music, where The Philadelphia Orchestra performs. I am now enough of a music fan that I buy a twenty-five-dollar ticket to hear a famous orchestra play the "Eroica," Beethoven's third symphony, live. It is not a very heroic experience. I feel dispirited from the moment I walk in the hall. My black jeans draw disapproving glances from men who seem to be modeling the Johnny Carson collection. I look around dubiously at the twenty shades of red in which the hall is decorated. The music starts, but I find it hard to think of Beethoven's detestation of all tyranny over the human mind when the man next to me is a dead ringer for my dentist. The assassination sequence in the first movement is less exciting when the musicians have no emotion on their faces. I cough; a thin man, reading a dog-eared score, glares at me. When the movement is about a minute from ending, an ancient woman creeps slowly up the aisle, a look of enormous dissatisfaction on her face, followed at a few paces by a blank-faced husband. Finally, three grand chords to finish, which the composer obviously intended to set off a roar of applause. I start to clap, but the man with the score glares again. One does not applaud in the midst of greatly great great music, even if the composer wants to! Coughing, squirming, whispering, the crowd visibly suppresses its urge to express pleasure. It's like mass anal retention. The slow tread of the Funeral march, or Marcia funebre, as everyone insists on calling it, begins. I start to feel that my newfound respect for the music is dragging along behind the hearse.But I stay with it. For the duration of the Marcia, I try to disregard the audience and concentrate on the music. It strikes me that what I'm hearing is an entirely natural phenomenon, nothing more than the vibrations of creaky old instruments reverberating around a bow translates into a strand of sound; what I see is what I hear. So when the cellos and basses make the floor tremble with their big deep note in the middle of the march (what Bernstein calls the "wham!") the force of he moment is purely physical. Amplifiers are for the gutless, I'm starting to think. The orchestra isn't playing with the same cowed intensity as on the Otto Klemperer recording I own, but the tone is warmer and deeper and rounder than on the phonograph record. I make my peace with the stiffness of the scene by thinking of it as a cool frame for a hot event. Perhaps this is how it has to be: Beethoven needs a passive audience as a foil. To my left, a sleeping dentist; to my right, an angry aesthete; and, in front of me, the funeral march that rises to a fugal fury, and breaks down into softly sobbing memories of themes, and then gives way to an entirely new mood -- hard-driving, laughing, lurching, a little drunk.

No comments:

Post a Comment