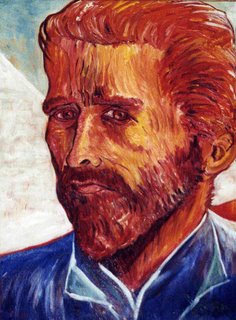

How does the artist create himself? How does the artist transform his common, conventional state to one of artistic awareness. How does the artist train his senses to accept those necessary but forbidden impulses or trivial ideas that exist outside human reason and put them to creative use? Let me give you some advice:

How does the artist create himself? How does the artist transform his common, conventional state to one of artistic awareness. How does the artist train his senses to accept those necessary but forbidden impulses or trivial ideas that exist outside human reason and put them to creative use? Let me give you some advice:It is so important to be lonely and attentive when one is sad: because the apparently uneventful and stark moment at which our future sets foot in us is so much closer to life than that other noisy and fortuitous point of time at which it happens to us as if from outside. The more still, more patient and more open we are when we are sad, so much the deeper and so much the more unswerving does the new go into us, so much the better do we make it ours, so much the more will it be our destiny.

The artist must be open to a state of reverie, which suggests an opening up the sense of wonderment. Reverie removes us from reality, entering areas even more intense that interiority. In this respect, reverie has phenomenological overtones: through reveries and poetic image we gain insight into the very workings of mind and imagination, what Shelley meant when he said that imagination is capable of "making us create what we see." Reverie negates pure representation and transcription. It struggles against fact and data. It is an effort to burrow into pure memory, which is distinguishable from sensation, which is "extended and localized." Pure memory is intensive and powerless, beyond movement and beyond sensation. It allows penetration into spirit, into intuition. What is necessary, above all, is to separate memory from cerebralism. Cerebralism leads to the adoption of reference points, objects, relationships; what emanates from pure memory allows one to possess objects, surely to transform them.

It seems a bad thing and detrimental to the creative work of the mind if reason, or cerebralism, makes too close an examination of the ideas as they come pouring in -- at the very gateway, as it were. Looked at in isolation, a thought may seem very trivial or very fantastic; but it may be made important by another thought that comes after it, and, in conjunction with other thoughts that may seem equally absurd, it may turn out to form a most effective link. Reason cannot form any opinion upon all this unless it retains the thought long enough to look at it in connection with the others. On the other hand, where there is a creative mind, reason -- so it seems to me -- relaxes its watch upon the gates, and the ideas rush in pell-mell, and only then does it look them through and examine them in a mass. The noncreative person is ashamed or frightened of the momentary and transient extravagances which are to be found in all truly creative minds and whose longer or shorter duration distinguishes the thinking artist from the dreamer. The non-artist complains of the fruitlessness of trivial ideas because he rejects too soon and discriminates too severely.

If you wish to be an artist, be open to yourself and the world about you. Accept those trivial ideas, fantastic imaginings, and forbidden impulses which are inimical to social convention as necessary raw material and building blocks for creative activity!

No comments:

Post a Comment