It seems to me that upbringings have themes. The parents set the theme, either explicitly or implicitly, and the children pick it up, sometimes accurately and sometimes not so accurately. When you hear people talking about their children, you can often detect a theme. The theme may be "Our family has a distinguished heritage that you must live up to," or "We are suffering because your father deserted us," or "No matter what happens, we are fortunate to be together in this lovely center of the earth," or "There are simply too damn many of us to make this thing work." Sometimes there is more than one theme. It's possible, for instance, for an upbringing to reflect at the same time "We are suffering because your father deserted us" and "There are simply too damn many of us to make this thing work."

It seems to me that upbringings have themes. The parents set the theme, either explicitly or implicitly, and the children pick it up, sometimes accurately and sometimes not so accurately. When you hear people talking about their children, you can often detect a theme. The theme may be "Our family has a distinguished heritage that you must live up to," or "We are suffering because your father deserted us," or "No matter what happens, we are fortunate to be together in this lovely center of the earth," or "There are simply too damn many of us to make this thing work." Sometimes there is more than one theme. It's possible, for instance, for an upbringing to reflect at the same time "We are suffering because your father deserted us" and "There are simply too damn many of us to make this thing work."When I was a child, I was under the impression that one of the themes of my upbringing was one of the grand American themes: "We have worked hard so that you can have the opportunities we didn't have." It's a grand theme partly because in its purest form it requires a suppression of ego: it requires people to think of their lives as taking meaning largely from being a transition to other people's lives--their children's. Thinking back on it, though, I realize that I might have misread the signals slightly. I think what was actually being presented was the immigrant subsection of that theme: "We have worked hard so that you can have the opportunity to be a real American."

Our immediate family would not have struck anybody as foreigners. Both my father's parents and my mother's parents were born in Europe, but my parents were thoroughly American and did not even speak the language of their parents. We didn't live in an immigrant neighborhood; but I suspect that a lot of people I went to school with had grandparents who came from Europe. But the Old Country -- untalked about, basically unexperienced by anyone in our immediate family --was a constant in our lives. My mother was born in West Virginia, but her parents were Polish-Catholic immigrants. Her father had one of those bone-chilling immigration stories often heard among people of that generation. Having immigrated to America from Poland to work as a coal miner, in about 1910, he died in the prime of his life in 1918 in the great influenza epidemic that swept the country, indeed, the world, following World War I.

We used to go to Atlantic City every summer when I was a boy. To some degree I associated Atlantic City with immigrants. In the late 1950s, about fifteen years after the end of World War II, Atlantic City was a vacation refuge for many holocaust survivors. The numbers stamped on the arms of survivors were always prominent in their beach attire. I remember asking my mother as a small boy on the beach about all the people with numbers stamped on their arms. "Sh," my mother would say. "They were in concentration camps." "What are concentration camps?" "Sh," my mother would repeat. I knew I had stumbled onto a forbidden subject.

My father's immigrant parents had died years before I was born. The only person one generation older than my parents who survived into my childhood was my mother's mother, who spoke English with a heavy accent. By chance, the only other old person I saw regularly when I was a boy also had an accent; the mother of my father's friends with whom we stayed each year in Atlantic City.

Only one generation removed from me, my father had grown up in an entirely different world. His was a world populated by immigrants. He had a friend, Benny Rossman whose household was a free-wheeling, lively place filled with Yiddish talk and Yiddish newspapers which, at first, neither of his parents could read. My father was one of the many people always stopping by the Rossman household, some living there for a few months if they had no work . . . always good food. My father used to drop by the Rossman's house for fried matzoth and to hear his friend Benny's father sing songs in Hebrew and Yiddish. Benny, the youngest son, was early assigned the task of asking the four traditional questions at the yearly Seder, the Passover feast, held in the Rossman house as a mark more of tradition and of generational continuity than of religious observance.

My father had an American's optimism -- the sort of quiet confidence about the future that was not always easy to find among the immigrants or first-generation Americans of that era. The people who came to this country in the great wave of immigration from Europe may have looked on America as the land of opportunity, but their experience over generations in the Old Country must have told them that they would be doing well to keep their heads above water. One part of them was waiting for their American disaster. A story is told that in one immigrant home at the close of the Passover seder, at the moment when it was traditional in Jewish homes to offer in the final prayer the phrase "Next year in Jerusalem," the father would push back from the table and say, in Yiddish, "Iber a yor nischt erger" -- "Next year no worse."

1 comment:

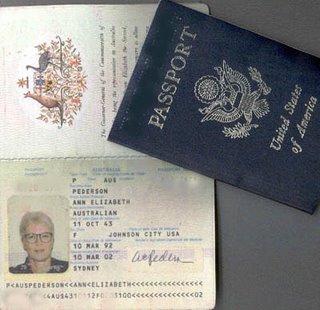

Shiv Reddy kindly advised that a previous post contained a photo of an Indian passport. I corrected for the error, and thank Mr. Reddy for his communication.

Post a Comment