My street in Washington is named for a New England state that is represented in Congress by one Orthodox Jewish senator and another senator who is reputed to be making tentative steps toward embarking on a presidential bid in 2008. It's a long street that traverses Washington, D.C. and wends its way deep into the northern suburbs of the city, way past the beltway. It's Connecticut Avenue, no more or less attractive than any other streets in the District that are named for New England states, though I must say I prefer Connecticut Avenue in Atlantic City where I once purchased three hotels in a ten-hour Monopoly marathon back in the 1960s.

If you didn't know it already, I'm a plagiarist. I plagiarize for fun but without profit. It's a hobby of mine, copying the writings of others and passing them off as the writings of others. I'm an honest plagiarist. There aren't many of those. Most plagiarists copy the writings of others and pass those writings off as their own. Not me. Only the unsuspecting or the dedicatedly stupid would fail to notice the disclaimer at the heading of this blog that proclaims: "This blog features unattributed quotations and paraphrases of published material." Right now I'm plagiarizing or paraphrasing a piece from The New Yorker written by David Sedaris. But the paraphrasing is so thoroughgoing that you'd never know that this post is thoroughly unoriginal. The first sentence of the Sedaris piece, paraphrased above, reads: "My street in Paris is named for a surgeon who taught at the nearby medical school and discovered an abnormal skin condition, a contracture that causes the fingers to bend inward, eventually turning the hand into a full-time fist." (You can look up the piece yourself. It's in the April 18, 2005 edition of The New Yorker, starting at page 92.)

Now that's thorough plagiarizing. It goes beyond plagiarizing, in fact. My piece is more like a jazz riff on Sedaris. A totally inscrutable disguise that is only suggested by the published work.

I've never mentioned it before, but my plagiarizing has made me notorious in Washington, among both natives and tourists. People gather outside my window arguing about the merits of my work, or roundly condemn my linguistic practices, which are seen by some as the gravest of misdeeds -- crimes, really -- that call for nothing less than a sound whipping. I live on the first floor of my apartment building and the voices just below my window are easily heard amid the traffic noises emanating from that street I live on that's named for a New England state.

For some, the arguments are about language. A wife had made certain claims regarding my abilities as a plagiarizer. "I've been reading his blog posts," she said, or, perhaps, "All those bloggers write things that are pretty much alike, so what's the difference if he copies from someone else?" But then people use slang, or ask unexpected questions, using obscene expletives and things begin to fall apart: "He's the one who claims to be a fucking original. He's an asshole." I hear this all the time, and look out my window to see a couple standing toe to toe on the sidewalk.

"Yeah," the woman will say. "But at least he tries to write something that sets him apart from other bloggers. That should count for something in the blogosphere."

"Well, he should try harder, damn it. Nobody wants to read what somebody else has already written."

Arguments about the sources of material are the second most common. People notice that they've read something before and argue about where they've read it. Was it in high school English, in college? What is it that I've plagiarized? Is it Dickens, Chaucer, Shakespeare? These arguments will last about half an hour, then the couple will decide they are tired and hungry and need to find a bathroom. That's the thing about plagiarism. It only concerns people who have nothing else to worry about. If you're tired, hungry, or need to use a toilet facility, someone else's act of plagiarizing has about as much interest as yesterday's garbage. People argue about plagiarism only when they have nothing else to argue about. Plagiarizing and paraphrasing is way down on the totem pole of people's concerns. Get hit with a cancer diagnosis, and I guarantee you, you won't be arguing about whether or not I plagiarize.

"For God's sake, Philip, would it kill you to just ask somebody where you've read this piece before?"

I lie on my couch thinking, Why don't you ask? How come Philip has to do it? But these things are often more complicated than they appear. Maybe Mary Frances was an English major, and has been claiming to have an encyclopedic knowledge of English literature. Maybe she's one of those who refuse to investigate cases of suspected plagiarism lest she appear to be not as knowledgeable as she's always claimed.

The desire to pass as a literary authority is loaded territory, and can lead to the ugliest sort of argument. "You want to be considered to have a vast knowledge of world literature, Mary Frances, that's your problem, but you're just another illiterate." I went to the window for that one, and saw a marriage disintegrate before my eyes. Poor Mary Frances in her beige beret. Back at the hotel it had probably seemed like a good idea, but now it was ruined and ridiculous, a cheap felt pancake sliding off the back of her head. She'd done the little scarf thing, too, not caring that it was summer. It could have been worse, I thought. She could have been wearing one of those striped boater's shirts, but, as it was, it was pretty bad, a costume, really. Yes, here was poor Mary Frances fretting about my supposed plagiarism when she herself looked like a walking caricature. A case of sartorial misrepresentation. She was dressed like every other damned female tourist in Washington and here she was worried about the fact that my latest blog post seemed to resemble something she had read in a tenth-grade English class.

Some vacationers raise the roof -- they don't care who hears them -- but Mary Frances spoke in a whisper. This, too, was seen as pretension, and made her husband even angrier. "Bloggers," he repeated. "They write trash anyway. What's the difference if some blogger outsources his blog posts? Got it?"

I looked at this guy and knew for certain that if we'd met at a party he'd claim to have never noticed my plagiarism. No, he'd never have the balls to do that. He might have to admit that although my blog posts seemed unoriginal, he couldn't quite figure out whether he'd read my material in The New Yorker or in the New York Times travel section. Besides there was the issue of his own attire. How would he explain that some other guy at the party was wearing the exact same necktie.

As a white man, you can live your whole life never not fitting in. You never walk into a bar that sees only your boobs. To be Whitie is to be wallpaper. You don't draw attention, good or bad. Still, what would it be like, to live with attention? To just let people stare. To let them fill in the blank, and assume what they will. To let people project some aspect of themselves on you for a whole day.

As a white man, you can live your whole life never not fitting in. You never walk into a bar that sees only your boobs. To be Whitie is to be wallpaper. You don't draw attention, good or bad. Still, what would it be like, to live with attention? To just let people stare. To let them fill in the blank, and assume what they will. To let people project some aspect of themselves on you for a whole day.

In the summer of 1983, at the age of 29, I moved to Washington, DC and entered the Master of Laws Program at American University Law School. This wasn't exactly the culmination of a lifelong dream. I'd come to Washington to become managing partner of a major law firm, and, in fact, I'd been signed two years earlier as a law clerk by Sagot & Jennings, one of the more reputable law firms in Philadelphia. I thought the line from law clerk to managing partner would be straight and short. But other than occasional rejection letters, I wasn't making much progress, and I was beginning to wonder why I'd ever left Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

In the summer of 1983, at the age of 29, I moved to Washington, DC and entered the Master of Laws Program at American University Law School. This wasn't exactly the culmination of a lifelong dream. I'd come to Washington to become managing partner of a major law firm, and, in fact, I'd been signed two years earlier as a law clerk by Sagot & Jennings, one of the more reputable law firms in Philadelphia. I thought the line from law clerk to managing partner would be straight and short. But other than occasional rejection letters, I wasn't making much progress, and I was beginning to wonder why I'd ever left Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

This post is dedicated to Brad M. Dolinsky, M.D.

This post is dedicated to Brad M. Dolinsky, M.D.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE:

DRAMATIS PERSONAE:

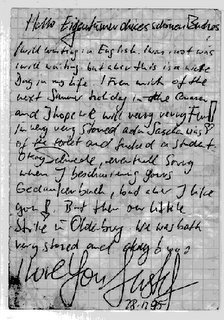

I have become lost to the world with which I wasted so much time; it has heard nothing from me for so long that it may well think that I am dead!

I have become lost to the world with which I wasted so much time; it has heard nothing from me for so long that it may well think that I am dead!